We have officially entered the age of the efficiency paradox.

The era of cheap, abundant capital is over.

CMOs face a dual mandate: deliver record-breaking yet durable growth for the CEO, while defending every dollar of spend to a CFO and Board who speaks an entirely different language of ROI, margin, and payback.

Today’s business market is volatile, meaning the speed of change makes a “set-and-forget” annual marketing budget obsolete. What’s required instead is a more flexible mindset, one that shifts marketing away from being viewed as a cost center and toward being treated as a diversified investment portfolio that contributes directly to EBITDA and enterprise value.

To navigate this paradox, CMOs must view their budgets, not as spend, but as a collection of investment assets aligned to a single company objective.

In this article, we’ll explore the brand versus performance balance, the 70/20/10 framework, and the operational rigor required to turn marketing budgets into long-term enterprise value.

The brand vs. performance tension

One of the most common mistakes CMOs make is over-investing in short-term performance at the expense of long-term brand equity.

Research popularized by Binet and Field suggests a baseline split of roughly 60/40 between brand and performance, though the ideal mix varies by industry. Consumer brands may skew more heavily toward brand, while B2B organizations often operate closer to balance.

Regardless of the ratio, brand remains a critical driver of enterprise value.

Strong brand equity improves marketing efficiency across the funnel – increasing click-through rates, improving conversion, and lowering blended CAC. In this sense, brand acts as a CAC subsidy and should be treated as a financial lever, not a soft metric.

Performance channels, however, have ceilings. Once in-market demand is captured, CAC rises and returns flatten. Rising costs alongside stagnant revenue signal a performance plateau. Brand investment builds out-of-market awareness, ensuring your company is top of mind when buyers re-enter the category.

Strategic alignment: Speaking the language of the board

One of the most common reasons marketing budgets are reduced or eliminated is simple: marketing is often communicated in tactical metrics instead of financial outcomes. This creates a translation gap in the boardroom, one that leaves marketing vulnerable.

CMOs must reposition the marketing budget as an asset, not an expense. The conversation needs to shift from “What will this campaign cost?” to “What marketing assets are we building that increase enterprise value?”

If a marketing leader cannot explain their budget in terms of EBITDA impact, margin contribution, or long-term value creation, the work is not finished. Successful board-level conversations are most productive when marketing leaders focus on how the budget aligns to corporate goals, growth, and enterprise value.

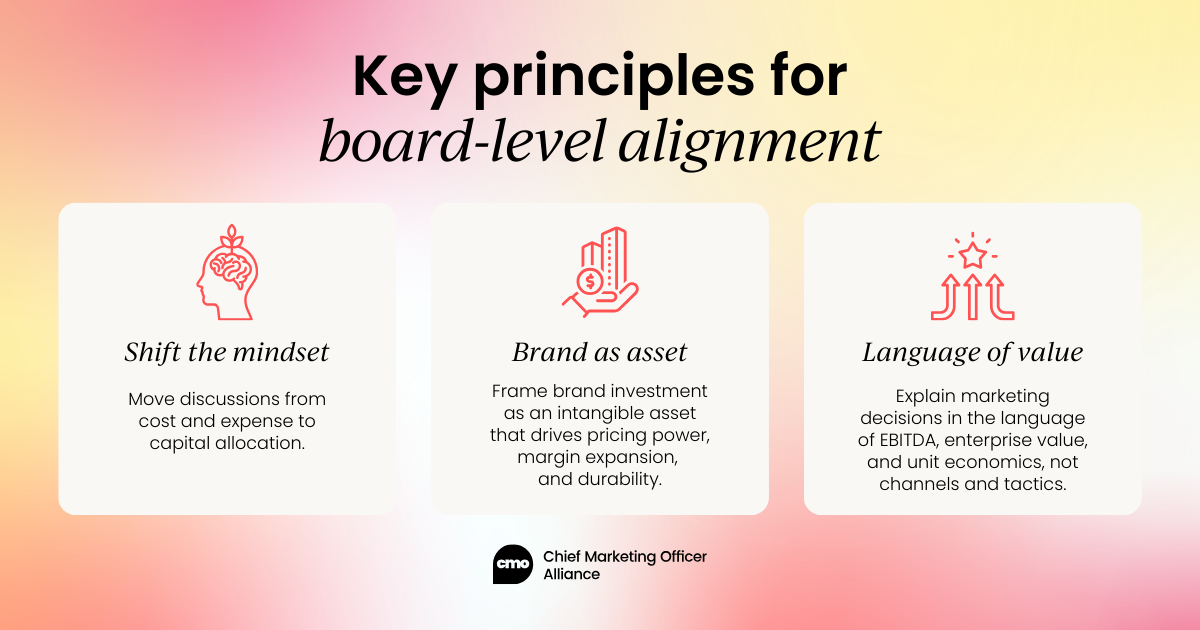

Key principles for board-level alignment include:

- Shift the mindset: Move discussions from cost and expense to capital allocation.

- Focus on the balance sheet: Frame brand investment as an intangible asset that drives pricing power, margin expansion, and durability.

- Lead with finance: Explain marketing decisions in the language of EBITDA, enterprise value, and unit economics, not channels and tactics.

Budget sizing: Context over percentages

Rather than anchoring on arbitrary benchmarks, marketing budgets must be contextualized within the company’s lifecycle and strategic priorities.

In high-growth phases, the business may accept higher CAC and lower short-term profitability in exchange for speed and scale. In more mature or efficiency-driven phases, LTV expansion and margin improvement become the priority. When competition intensifies, brand investment becomes a defensive moat to protect market share and pricing power.

While benchmarks can be helpful, context matters more:

Average companies: 7.7%–9.1% of revenue

This range typically reflects companies operating in relative stable markets with modest growth, with a balance between efficiency and expansion. Companies in this range often have established channels, predictable unit economics, and at times, limited appetite for aggressive experimentation.

Hyper-growth: 15%–21% of revenue

This allocation is common in companies that are prioritize rapid market growth or capture, category expansion, or geographic expansion. This allocation should not be considered “inefficient marketing”, but a deliberate capital deployment for long term growth objectives and enterprise value.

Low-margin or defense mode: 2%–4% of revenue

This range is very common in companies that operate under margin pressure, increased competition, or economic or market uncertainty. Speculative and expansionary spend is minimized, while brand investment is often focused as defensive rather than a growth lever.

Unit economics: Tying every dollar to value creation

If the company spends $1 on marketing, what is the return, and how quickly?

Boards ultimately think in unit economics.

While not every organization operates on a pure SaaS model, marketing payback period is widely accepted as a universal metric.

From a unit economics perspective, a useful benchmark for boards is a 1.0 marketing efficiency ratio, where new revenue generated in a given period equals to the prior quarter’s marketing investments. This would signal that marketing capital is being used efficiently back into the business.

In a B2B environment, a CAC payback period of 12 to 19 months is generally considered healthy and reflects a balanced trade-off between growth and capital discipline.

Counterintuitively, a payback period of under six months often indicates underinvestment rather than efficiency. This can be a sign that the company may be overserving existing demand, missing opportunities to capture additional market share, and constraining long-term growth by prioritizing short term results.

An increasingly important metric for CMOs is incremental margin contribution, demonstrating how marketing enables revenue growth more efficiently than adding sales headcount, improving overall margins.

When CMOs understand and articulate unit economics, ROI conversations with the board become materially more productive.

The 70/20/10 framework: Balancing risk and reward

70%: Core performance – The revenue engine

This is the foundation of the budget: proven, predictable channels that consistently generate ROI. The focus here is efficiency, conversion, and retention.

Common examples include SEO, SEM, email, CRM, and established lead-generation tactics. These channels require optimization, not reinvention. The goal is to extract maximum margin from every dollar and use that efficiency to fund growth and experimentation elsewhere.

20%: High-potential growth – Scaled experiments

This is an offensive spend. These initiatives have shown early signs of success but require additional capital to prove scalability.

Examples include emerging social platforms, influencer programs, new geographies, or mid-funnel initiatives. This is where growth lives, but only when tested with rigor and clear performance thresholds.

10%: R&D sandbox – Future growth bets

This portion of the budget is intentionally speculative and often the first to be cut, yet it is critical for long-term resilience.

It funds high-risk, high-reward initiatives such as partnerships, emerging platforms, or early-stage technologies. Failure should be expected. This spend must be positioned internally and with finance as Research & Development, not discretionary experimentation.

Psychological safety is essential. Teams need to know that failure in this bucket is not only acceptable, but expected.

Keeping the budget agile: Rolling forecasts and kill switches

While strategy should remain stable, execution must be flexible. CMOs should reassess marketing spend and ROI on a quarterly basis rather than locking budgets annually.

This governance model allows for rapid reallocation, protecting the core 70% during downturns or increasing experimental spend when capital or opportunity arises.

Every initiative within the 20% and 10% must have pre-defined KPIs that determine when it should be accelerated or shut down. Capital should never sit idle. Underperforming initiatives must be quickly redeployed into proven channels.

This operational rigor creates a culture of honesty, speed, and accountability, one where teams are incentivized to surface truth, not defend sunk costs.

Finding your North Star

The final step in building a credible and defensible marketing budget is aligning it to one primary company objective, the North Star. Boards do not expect marketing to optimize for multiple, competing outcomes at once. They expect focus, intentional trade-offs, and clarity.

Whether the organization is prioritizing profitability, growth, market leadership, or capital efficiency, the marketing budget must be explicitly designed to serve that single objective. This alignment builds trust between the CMO, CFO, and board, and elevates marketing from discretionary spend to strategic lever.

Every line item in the budget should clearly ladder up to the North Star. If a tactic cannot be articulated in terms of how it advances the company’s primary objective, it becomes a vanity initiative and will not withstand scrutiny.

When the North Star is clear, the 70/20/10 framework becomes a unified portfolio rather than a collection of disconnected bets. The 70% supports the core objective, the 20% accelerates it, and the 10% explores future pathways that may serve the same goal over time.

The CMO as portfolio manager

The optimal marketing budget is neither purely analytical nor purely visionary. It is a disciplined blend of both.

Modern CMOs must act as portfolio managers – balancing proven performance with calculated experimentation. Those who succeed will earn their seat at the boardroom table by becoming the most financially fluent, data-driven leaders in the room.

The future of marketing belongs to CMOs who treat budgets not as spend, but as capital.

.png)

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow us on LinkedIn