If you’re a CMO, change management is already part of your job – whether it's written in your job description or not. Marketing rarely gets the luxury of stability. Priorities shift, channels evolve, budgets move, and leadership expectations change faster than most teams can comfortably keep up with.

Through all of that, you’re expected to maintain momentum while asking people to work in new ways.

At its core, change management is about helping people move from how things work today to how they need to work tomorrow.

That sounds straightforward, but anyone who’s led a marketing team knows it rarely feels that simple. You’re not just changing processes or tools; you’re changing habits, routines, and sometimes people’s confidence in their own role.

This is especially true in marketing organizations with multiple layers. You have individual contributors focused on execution, managers translating strategy into day-to-day work, and senior leaders expecting results quickly. If change isn’t handled carefully across those layers, misalignment shows up fast.

There’s also a consistent disconnect between intention and perception. Gartner found that 74% of leaders say they have involved employees in creating a change strategy, but only 42% of employees feel included. That gap matters. It’s often the difference between a team that adapts and one that quietly resists.

Where change shows up in a CMO’s world

Change doesn’t arrive in one form. As a CMO, it tends to show up in familiar patterns, even if the details differ each time.

Team structure and role changes

Reorganizations are one of the most common sources of disruption. You might be shifting from channel-based roles to lifecycle ownership, consolidating teams after growth, or adjusting responsibilities to better match where the business is headed.

On paper, these changes often make sense. In reality, they raise questions people don’t always ask out loud. Who owns what now? What does success look like in this new structure? Am I still valued in the same way?

If those questions go unanswered, uncertainty can quickly turn into disengagement, even among high performers.

Technology and tooling changes

New tools are another constant. CRM rebuilds, analytics platforms, project management systems, and AI-driven tools all promise efficiency, but they also disrupt established ways of working.

For many marketers, tools are closely tied to how they organize their day and measure their own effectiveness.

When a tool change is framed purely as a leadership or reporting need, adoption usually suffers. People need to understand how it makes their work clearer, easier, or more impactful – not just how it benefits dashboards.

Shifts in strategy or priorities

Strategic changes often create confusion because they don’t always come with immediate operational clarity. A renewed focus on brand, a tighter connection to sales, or a move toward long-term growth metrics can leave teams unsure how to adjust their daily decisions.

Without clear guidance, people default to what worked before, even if leadership has moved on. That gap between strategy and execution is where frustration builds.

External or forced change

Some change comes from outside marketing altogether. Budget cuts, leadership turnover, mergers, or new company-wide priorities can land suddenly and with little context. Even positive changes, like rapid growth, can strain teams if roles, processes, and expectations don’t evolve alongside them.

In these moments, your role often shifts from decision-maker to interpreter, helping your team understand what the change means for them specifically.

What to keep in mind when leading through change

Resistance rarely comes from stubbornness. More often, it comes from uncertainty.

Oak Engage’s research shows that mistrust in the organization is the biggest driver of resistance at 41%, followed closely by lack of understanding around why change is happening (39%) and fear of the unknown (38%). Concerns about role changes and exclusion from decisions also play a significant role.

One of the most effective ways to reduce resistance is by involving people earlier than feels strictly necessary.

That doesn’t mean opening every decision to debate, but it does mean inviting input while things are still taking shape. People are far more likely to support change when they recognize their perspective in the outcome.

Clarity also matters more than polish. If the reason for change isn’t explicit, people will create their own explanations, and those explanations tend to be more negative. Be clear about what’s changing, why it’s happening now, and what is staying the same. That last piece is often overlooked, but it gives people something stable to hold onto.

It also helps to be honest about uncertainty. Admitting that some details will be figured out along the way builds more trust than pretending everything is already solved.

Practical change management models for CMOs

You don’t need to be fluent in formal change theory to lead change well, but having a few simple models in mind can make your decisions more intentional.

These frameworks are useful because they give you a way to slow down, think through where people might struggle, and adjust your approach before problems show up.

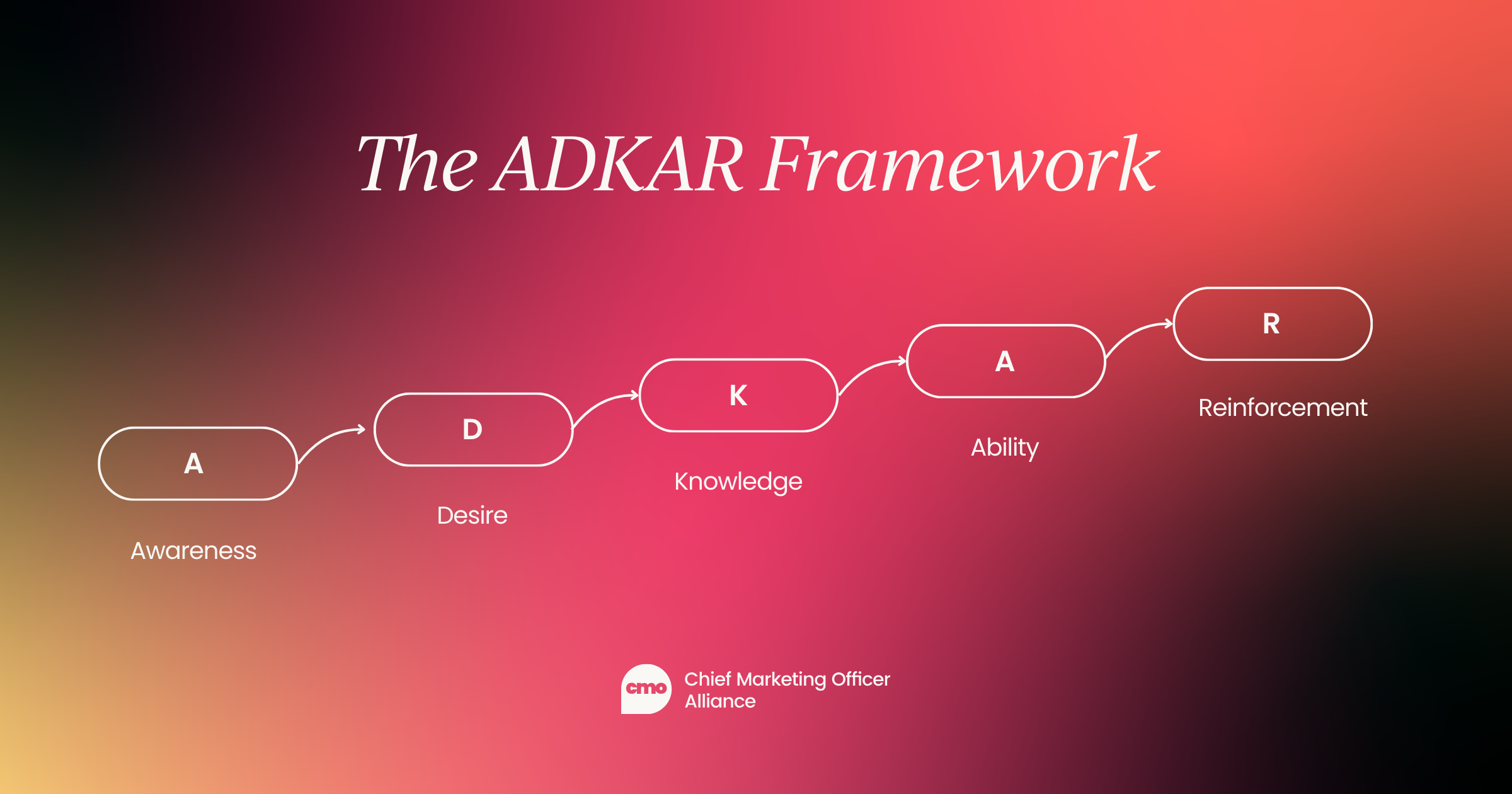

1. ADKAR

ADKAR focuses on Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement. It’s useful when rolling out new tools or processes.

For example, if you’re introducing a new campaign management platform, start by making sure everyone understands why the old system isn’t working. Then, build desire by showing how the new one helps their day-to-day work, not just reporting.

Training addresses knowledge, ongoing support builds ability, and regular check-ins reinforce the change over time.

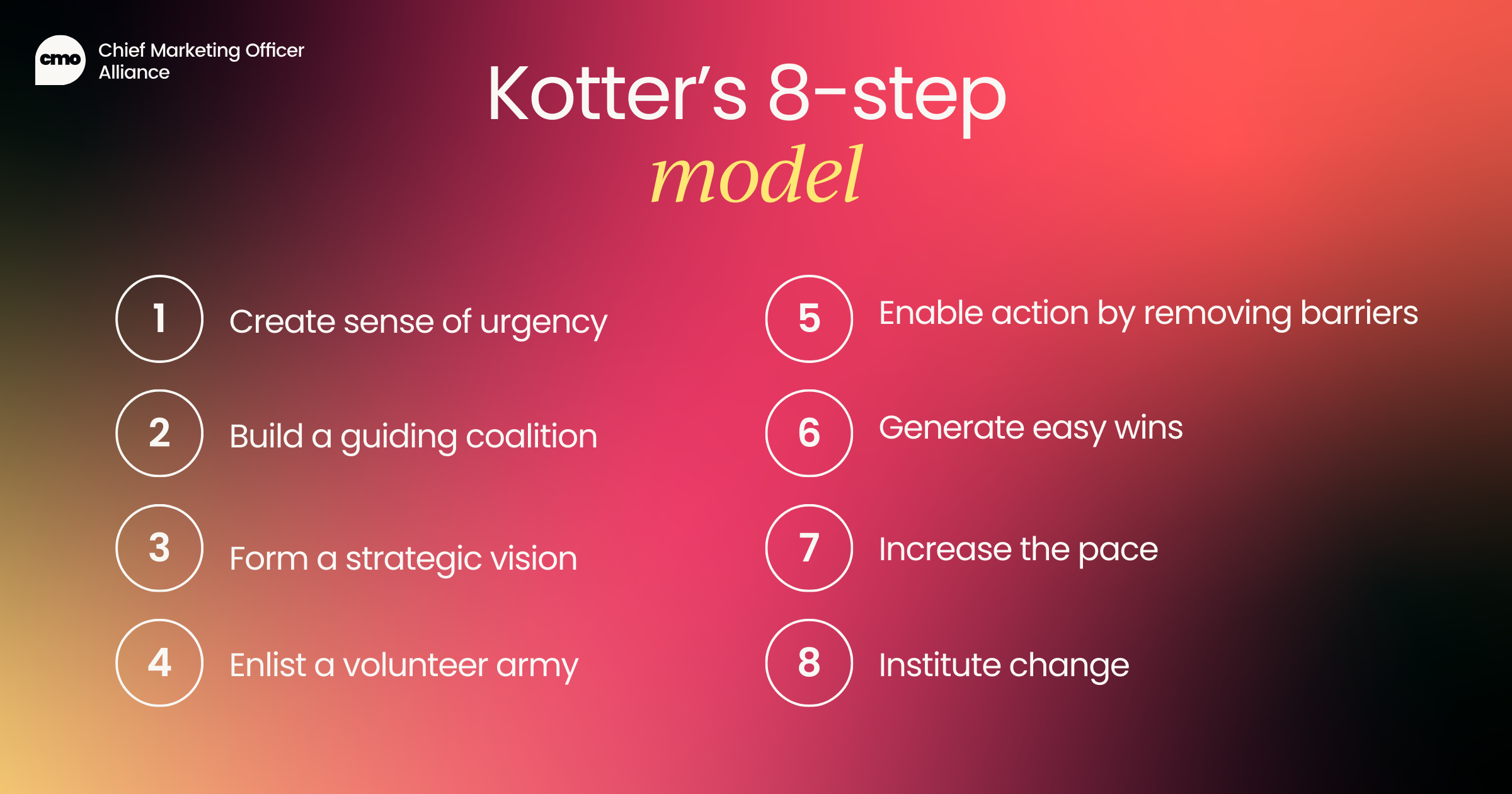

2. Kotter’s 8-step model

Kotter’s model is most helpful when you’re dealing with larger, more visible change, such as a full team restructure or a major shift in how marketing operates within the company. The biggest value here is that it forces you to think about sequencing, not just outcomes.

As a CMO, this often means resisting the urge to jump straight to execution. Before announcing a new structure, for example, you need genuine alignment across your leadership team and managers.

If they don’t understand the reasoning or can’t explain it clearly, the message will fracture as it moves through the organization.

Kotter’s emphasis on short-term wins is also especially relevant in marketing. If you’re changing how teams work together, look for early signals that things are improving – such as faster approvals or clearer ownership – and call those out. Small proof points help people believe the change is worth the effort.

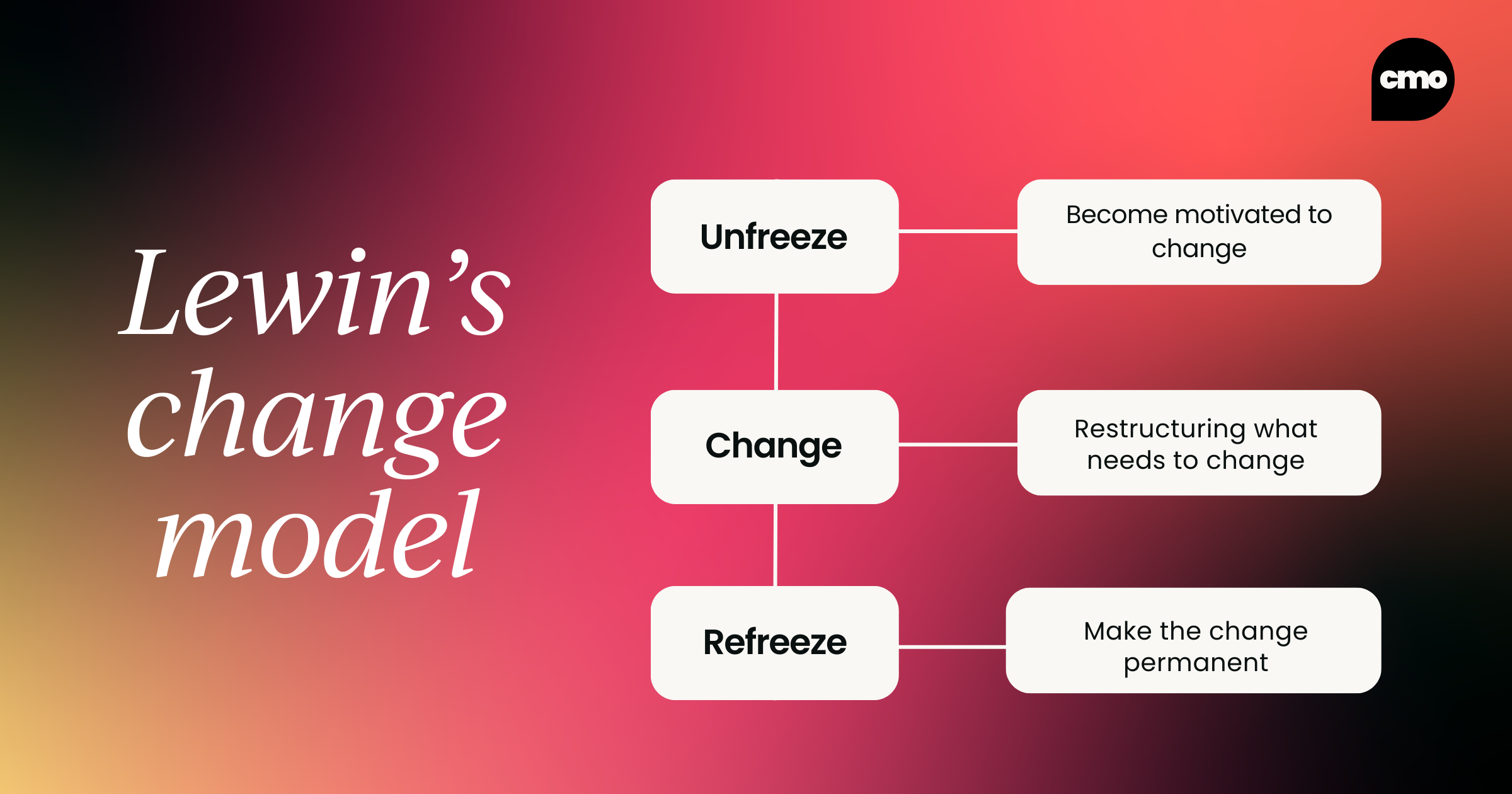

3. Lewin’s change model

Lewin’s model breaks change into three phases: unfreezing, changing, and refreezing. While it’s simple, it addresses one of the most common mistakes CMOs make: layering new ways of working on top of old ones.

In practice, unfreezing means explicitly letting go of behaviors or processes that no longer serve the team.

For example, if you’re introducing a new briefing process, you also need to clearly state that the old one is no longer being used. If that step is skipped, teams often end up maintaining both, which creates frustration and extra work.

The refreezing stage is just as important. Once the change is in place, reinforce what “good” now looks like. Update documentation, adjust onboarding, and make sure managers are modeling the new behavior. Otherwise, people tend to drift back to familiar habits, especially under pressure.

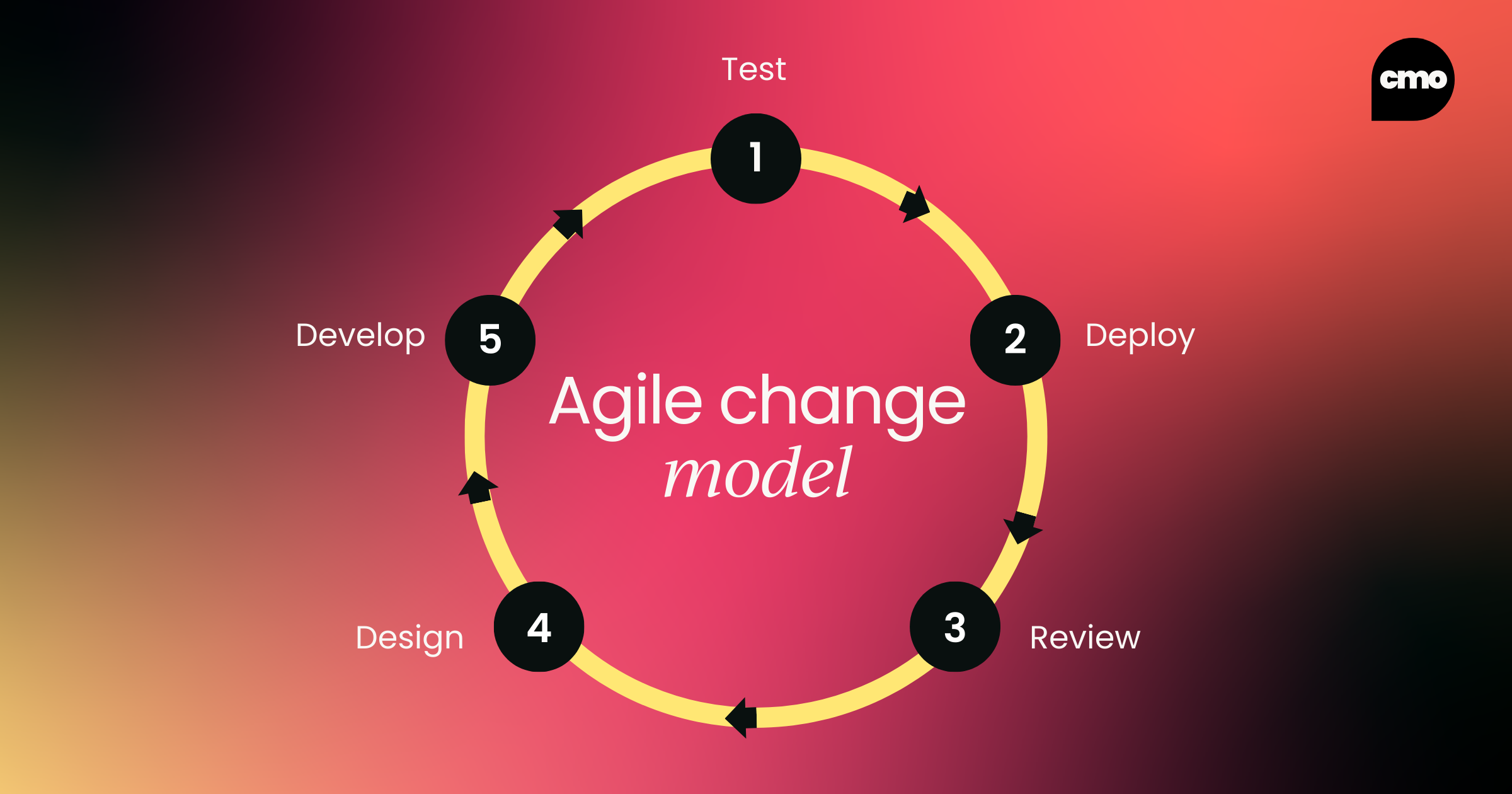

4. Agile change

Agile change is often the most natural fit for marketing teams because it mirrors how they already work. Instead of treating change as a one-time rollout, it’s approached as a series of small experiments.

For example, if you’re trying to improve collaboration between brand and performance teams, you might pilot a new planning cadence with one group rather than rolling it out across the entire department. You learn what works, adjust what doesn’t, and then expand gradually.

This approach reduces risk and lowers resistance. People are more open to trying something new when it’s framed as a test rather than a permanent decision. Over time, these smaller changes add up to meaningful transformation without overwhelming the team.

Metrics that show whether the change is actually working

According to the CEB Corporate Leadership Council, 51% of managers and employees say leaders don’t outline clear success metrics for change. Without those signals, teams don’t know whether they’re on track or just busy.

Focus on a small set of indicators:

- Adoption rates, usage patterns, and confidence levels often tell you more than formal KPIs.

- Short pulse surveys can help if you act on what you learn.

- Operational signals like cycle times, error rates, or campaign throughput also offer insight into whether change is improving how work gets done.

Navigating change when resources are limited

Limited time, budget, and headcount are common constraints.

ChangingPoint found that 65% of UK managers feel they lack the resources to manage change effectively, while Capterra reports that 83% of employees experiencing change fatigue don’t feel adequately supported.

When resources are tight, prioritization matters more than ambition. Focus on changes that remove friction rather than layering on new complexity. Make sure that you also identify trusted team members who can act as informal champions and support others through the transition.

Don’t forget, your biggest tool is to reuse what you already have. Plus, peer-led sessions, shared documentation, and recorded walkthroughs often feel more approachable than formal training programs.

Above all, be transparent about constraints. People are generally more understanding when they know why support is limited and what you’re doing to address it. Again, keeping things from your employees can build resentment. If there’s no reason to hide things, then why would you?

Following up after a change is implemented

The work doesn’t stop once a change is officially live. In many cases, this is the point where things either settle into a new normal or quietly slip back to how they used to be. How you show up in the weeks that follow matters just as much as how you handle the rollout.

Regular check-ins are one of the simplest and most effective tools you have. These don’t need to be formal or time-consuming.

What matters is creating space for people to talk honestly about what’s working, what feels awkward, and what’s getting in the way. When feedback leads to visible adjustments, even small ones, it sends a clear signal that you’re paying attention and that the change isn’t just a passing initiative.

It’s also important to deal with friction early. Minor issues have a way of becoming convenient excuses to fall back into old habits, especially when deadlines pile up. If a new process feels slower or a tool isn’t set up quite right, addressing that quickly helps maintain momentum and reinforces that the new way of working is the expected one.

Also, recognition plays a bigger role here than many leaders realize. Adapting to change takes energy, and that effort isn’t always visible in metrics right away.

Celebrating teams or individuals who are leaning into the change, experimenting, and staying open reinforces the behavior you want to see, even before results fully materialize.

Finally, make a point of closing the loop. Revisit why the change was made in the first place and share what’s starting to improve, even if the picture isn’t complete yet. When people can connect their effort to real progress, they’re far more likely to stick with it and carry that mindset into the next change that inevitably comes along.

Final thoughts

As a CMO, you sit at the intersection of strategy and execution. Change management isn’t about perfect plans or dramatic announcements. Instead, it’s all about trust, clarity, and consistency over time.

So, it’s important to involve people earlier, communicate clearly, measure what actually matters, and, whatever you do, don’t disappear once the change goes live! When teams feel supported before, during, and after change, they’re far more likely to move with you rather than push back.

.png)

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow us on LinkedIn